Braess Paradox And Smartphone Navigator Applications

Published:

We used to believe that to have the best final product, we should make a competitive environment for all companies. This way they will do their best to provide us a high-quality product with the minimum cost. Although this intuition seems to be true all the time, there are some cases in which the best outcome happens when we restrict this type of competition between different companies. For instance, consider the competition between different navigation assistant applications such as Google Maps, Waze, etc. They are trying to always give you the best possible route. Otherwise, we probably will not use them again so they will become extinct! Although this competition seems very nice, in this post, I will explain how this competition can lead us to a bad outcome for the society of drivers!

Let’s talk about the competition between navigation apps first:

Of course, all of the navigator applications try to increase their customers by providing better features. One of the most important features is the ability to find the fastest route for each customer. So the applications are designed in a way that if there is a better shortcut, that shortcut will be get used for customers to tempt them to use the same application for the next time. (instead of any other competitor apps.)

In other words, because we only use the application that gives us the best route every time, all companies inevitably should try their best to give us the best route every time otherwise their product will not be used anymore!

As a result, after a while, aside from the specific application that each individual uses, each individual is trying to find the best route for himself. In the following, we will explain why this is a bad thing for society!

Let’s define Average Travel Time

In this setting, each person has an average travel time. (Since we don’t have any information about each individual, and because, roughly speaking, each region in the city is similar to other regions, we can assume that the situation for each individual is the same and symmetric, so this average time is the amount of time we need to put for each travel)

There is a question arising in this setting. Does using this app necessarily lead to our city having the lowest possible average travel time for each individual? Or we can do better?

Someone might think that if each individual tries to minimize his travel time in each travel, then he is using routes less than the time when he doesn’t. So on aggregate, this will be the best possible choice for each individual. But this is not necessarily true. (I know it might be a little confusing for the first time, but wait), I will explain it using a very famous example which is called Baraess Paradox.

Braess Paradox

(All of the images here are from Game Theory Alive book [1])

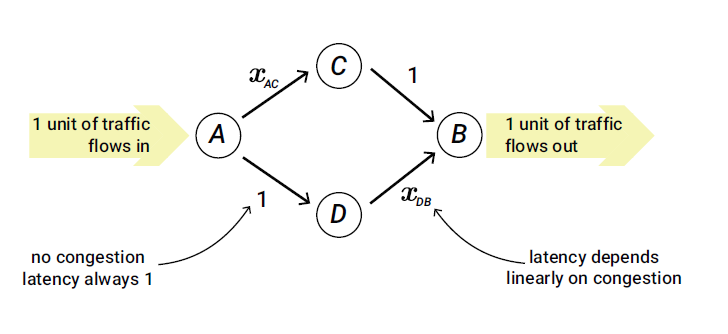

Suppose that we have 2 routes from A to B similar to the image below. Each edge in this graph has a latency function. We call it $l_e(x)$ where x is the number of cars in that edge.

Here, edges AD and CB have a constant latency function equals to one. $ l_{AD}(x)= l_{CB}(x)=1 $ (they represent streets which are sparse enough so that you can drive with the maximum speed of 30km/h without any trouble.)

Edges AC and DB have a latency proportional to the number of drivers that currently use that edge. $ l_{AC}(x) = l_{DB}(x) = x $ (You can assume that they are highways. On highways, you should keep your distance with the car in front of you in a way that if it immediately stopped, you would be able to react properly and stop your car. And the distance with that car is proportional to the number of cars using that route. i.e. If there are x cars on the highway, on average the car in front of you have d meter distance with you, on the other hand, if there are 2x cars, then on average the car in front of you have d/2 meters distance from you. so you need to decrease your speed from v to v/2 to keep your time distance with the car. as a result, the latency will increase from t to 2t.)

So in this setting, AC and DB are highways and we love to use them!

What will happen in this setting?

Ok so in that setting, what will happen? Suppose that $ 100.x $ percent of drivers like the top route and $ 100.(1-x) $ percent like the bottom route, then if $x\geq 0.5$ after a few days, those drivers who like the top route will notify that the bottom route is better, so they will lose their interest as time goes on. So we will see a decrease in the x population. If we plot the population for the top route each day, we will probably see a sequence converging to 0.5. If the $x\leq 0.5$ same things will happen to bottom route drivers.

So, after a few weeks, our expected latency would be:

1 + 0.5 for both top drivers and bottom drivers.

Adding a new road is not always good

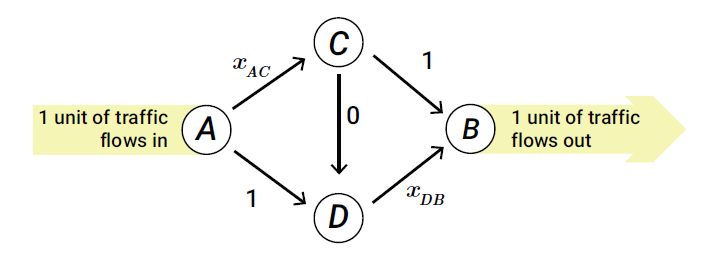

Now suppose we construct a shortcut from C to D with latency zero. Of course, adding a new line with no latency seems a good idea. People would love this. Because they can use the path A-C-D-B to use both of the highways. (Adding this shortcut is very similar to the situation in which people have access to a navigator app that knows local shortcuts from a highway to another. The app gives the best possible map for each individual that uses it)

Forget about the navigator app for a minute and suppose we are about to add our zero-latency shortcut.

What will happen?

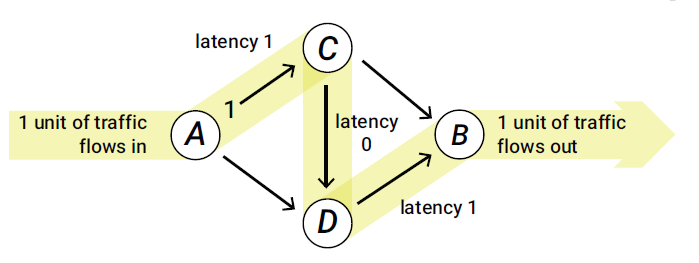

The day after we construct this shortcut, the drivers of the top route will notice that A-C-D-B is a faster route. So they will become interested to change their path. They will use A-C-D-B and the DB highway will become more crowded. As a result, the bottom drivers (A-D-B) will try to use the top route (A-C-D). As they use it, they will notice that there is a new shortcut C-D. They will test it and realize that the best path is A-C-D-B. Finally, after a couple of weeks, all drivers will use A-C-D-B as their path. (In fact, this choice is a Nash equilibrium, meaning that after a day, nobody will have any regret about the path he chose, also note that there might be several Nash equilibria) It means that all of the drivers use two highways and as a result, we have two crowded highways that are like streets. As if there is no highway at all! That’s a tragedy! So adding a shortcut is not always a good idea.

Getting back to our navigation problem

Adding a shortcut is in some sense related to the use of this navigation applications. Sometimes they give us shortcuts to get away from congested traffic. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that what we are doing to the traffic will not make the condition even worse for ourselves. Of course, this example is a very simplified model that cannot capture all the properties of a city. These linear latency functions are good to model network connection and not necessarily the best choice for traffic in cities. But aside from these simplicity making assumptions, there is a fundamental flaw when all people try to only maximize their objective. This might be the case that the

The best for the group comes when everyone in the group does what’s best for himself AND the group.

In the game theory community, people try to find a bound on how bad it is for people to be selfish comparing to the best average result. They call this bound price of anarchy.

Price of Anarchy

In the above example, the price of anarchy is:

\(\text{price of anarchy} =: \frac {\text{average travel time in the worst Nash equilibrium}}{\text{average travel time in socially optimum outcome}}=\frac{2}{\frac{3}{2}}=\frac{4}{3}\)

So in this simple city, if no one uses the shortcut, we can have a better travel time. Ok. Let’s talk about a better model for traffic.

A better model

I saw this model from Section 8.4 Atomic Selfish Routing from [1] (which is a very great book, at least for me). This model is closer to our city.

I brought the definition of it from [1]:

Consider a road network G = (V;E) and a set of k drivers, with each driver i traveling from a starting node $s_i \in V$ to a destination $ t_i \in V$ . Associated with each edge $e \in E$ is a latency function$l_e(n) = a_e . n+b_e$ representing the cost of traversing edge e if n drivers use it. Driver i’s strategic decision is which path $P_i$ to choose from $s_i$ to $t_i$, and her objective is to choose a path with minimum latency.

To what extent we can hope for a better application

In the setting above, the price of anarchy is at most $ \frac{5}{2} $ . [1] Meaning that if we use the best social optimum paths, then the best thing we can hope for is to decrease our average latency by a factor of $ \frac{2}{5} $. If we assume that the model above is precise enough, then $ \frac{2}{5} $ is a bound on how bad the navigation apps affect the traffic compared to the best possible routing system.

Conclusion: What is the solution

What we know so far is that, there is a possibility that the price of anarchy in our city would be a big number. So we should verify it. (Perhaps, by collecting data and estimating the latency function and distribution of starting and ending locations and computing the estimated price of anarchy).

Suppose that it is verified that the price of anarchy in our city is a big number. In this case, the competition between different companies leads to this anarchy. Right now they do not have any incentive to give the social optimum route to each individual. So I can propose two naive ways-of courses there should be better solutions:

1) Restrict people to use a central app which gives us social optimum routes

2) Charge individuals for the route they choose based on the effect it has on the average traffic time.

Maybe we can find a good price function to incentivize people to use social optimum routes. Similar to the ideas related to Mechanism Design.

Resources:

1: Karlin, Anna R., and Yuval Peres. Game theory, alive. Vol. 101. American Mathematical Soc., 2017.